Corruption Perceptions Index 2023 for Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Autocracy and Weak Justice Systems Enable Widespread Corruption

The Corruption Perceptions Index paints a worrying picture for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, an area struggling with dysfunctional rule of law, the rise of authoritarianism and...

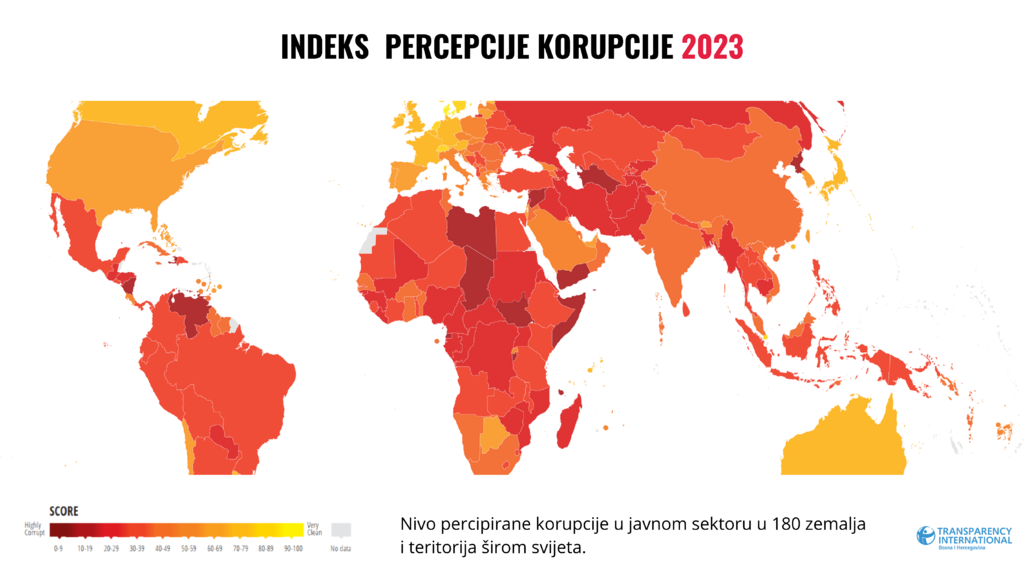

The Corruption Perceptions Index paints a worrying picture for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, an area struggling with dysfunctional rule of law, the rise of authoritarianism and systemic corruption. An average score of 35 out of 100 makes it the second lowest ranked region in the world.

The widespread decline of democracy and the weakening of judicial systems undermine the control of corruption, as institutions such as the police, prosecutors and courts are often prevented from investigating and punishing those who abuse their power.

In the region where war and inflation increase the level of poverty, it is essential that leaders act for the common good.

However, there are numerous examples where public officials systematically influence policies and institutions in order to increase their power and emblezzle public funds. Leaders urgently need to strengthen the rule of law, democracy and human rights, but many of them systematically endanger them.

The 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index shows that while most countries in Eastern Europe and East Asia are not making progress in the fight against corruption, five countries have significantly improved their Corruption Perceptions Index over the past 10 years. This shows that despite the significant challenges being faced by most of the region, changes are still possible.

The remaining countries are stagnating in their anti-corruption efforts, except for Bosnia and Herzegovina (CPI score: 35), Turkey (34) and Turkmenistan (18), which have regressed in the previous period. Turkey also achieved its lowest score on the Corruption Perceptions Index scale, as did Serbia (36), Russia (26) and Tajikistan (20).

Weak judiciary allows corruption to flourish

Across the region, multiple governments control the judiciary and law enforcement institutions in order not to punish those in their privileged circles for corruption.

For Georgia and the countries of the Western Balkans, these persistent practices stand in the way of membership in the European Union. This is also the case with Moldova and Ukraine, although these countries are implementing significant reforms in their judicial systems.

Putin’s regime’s long campaign to dominate Russia (26) and its resources has made corruption deeply rooted. The government largely controls public institutions, allowing widespread abuse of power without accountability.

The erosion of judicial independence in Russia has increased impunity for corrupt practices, seriously undermining public confidence in the justice system. The regime also uses this system to suppress the opposition, thus consolidating its power. The result is that the ruling elite can pursue destructive ambitions without restraint, and Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine shows how dangerous the consequences of uncontrolled power can be.

As soon as small signs of progress began to appear, the judiciary was significantly damaged by undemocratic changes and additions to the criminal code in North Macedonia (42). The decision to reduce penalties for abuse of office for personal gain and shortened deadlines for initiating court proceedings in cases of suspected corruption has done a great favor to corrupt individuals: it is estimated that around 200 cases will be dismissed, including those against former high-ranking officials.

Politically motivated appointments and dismissals of judicial officials raise additional concerns about the judiciary’s ability to effectively fight corruption. Due to susceptibility to political pressures, judicial systems in Bosnia and Herzegovina (35) and Serbia (36) are largely unable to prosecute and sanction public officials who abuse their position.

Weak laws, oversight institutions and reporting channels have also contributed to the steady decline in the Corruption Perceptions Index in these two countries.

Complex administrative and judicial structures in Bosnia and Herzegovina leave room for the concentration of power in the leading ethnic political parties. Their dominant influence on all branches of government contributes to systemic corruption and disrupts the very functioning of the state, which causes citizens to lose trust in institutions.

The vulnerability of prosecutors’ offices and courts to undue influence significantly undermines efforts in the fight against corruption, where major scandals remain unresolved.

This negative trend is exacerbated by the efforts of political elites to silence those who oversee the work of public institutions through newly enacted and proposed laws that criminalize defamation, target independent civil society, and sanction anyone who “disparages public authorities.”

Also, if adopted, the latest draft of the Law on Immunity would be an additional blow to the already weak rule of law in the Republic of Srpska. This would reduce the ability of the courts to hold public officials accountable, including deputies and members of the executive branch, and it would partly apply to previous criminal acts as well as new ones.

Country to observe: Moldova

With persistent efforts to strengthen democracy, the fight against corruption and the rule of law, Moldova (42) continues to improve steadily on the Corruption Perceptions Index – this year the country has advanced by another three points.

The key to reforms in Moldova is strengthening the independence and efficiency of the judiciary. It has taken significant steps to reduce judicial interference – including by politicians – to prevent manipulation of legal procedures and selective enforcement of laws.

Moldova has adopted a strong Law on Access to Information that promotes transparency in public sector activities. It also approved the National Integrity and Anti-Corruption Program for 2024-2028 with a corresponding action plan, clarifying its approach to future anti-corruption activities.

However, Moldova still faces external pressures, particularly due to its proximity to Russia and the war against Ukraine and its historical ties to Russia.

These pressures, including attempts of political and legal interference, have sometimes hindered reforms and increased the risks of corruption. Despite active efforts to limit the destabilizing influence of Russian-backed oligarchs, they have managed to inject significant funds into Moldova’s political system in an attempt to buy elections and divert the country from the path to EU membership.

The country has a long way to go before it has a highly effective anti-corruption framework, as indicated by weaknesses in its specialized anti-corruption bodies and problems with ensuring the integrity of elected officials. Policy making also needs to be better protected from undue influence.

Cooperation with the democratic international community remains crucial, providing basic resources and knowledge to strengthen institutional frameworks and fight corruption. Moldova must persist in reforms and effectively manage internal and external disturbances.

Autocracy undisputedly enables corruption or enables undisputed corruption* Ranked at the bottom of the index, Azerbaijan (23), Tajikistan (20) and Turkmenistan (18) continue to face serious corruption problems.

Authoritarian control over state institutions by ruling elites has become firmly entrenched, with corruption being used to maintain power and avoid accountability.

Low ratings of these countries reflect systematic governance deficiencies and a lack of independent oversight, where corruption undermines various levels of society and the state, simultaneously undermining civil and political rights.

In Georgia (53), corruption continues to be a problem, which points to a deeper systemic problem – the concentration of power and the pervasive influence of elites on state institutions and decision-making. Georgia has been going through a democratic backsliding for several years now, where deepening state capture and high levels of corruption are turning the government into a kleptocracy.

Another sign of this is the recent “return” to the active politics of Bidzina Ivanishvili, the founder of the ruling party, who was the key figure in the capture of the country’s institutions. Although it was once celebrated as a fighter against corruption, the problem of corruption in Georgia has grown to the extent that it is now one of the main obstacles to EU integration.

Although a new anti-corruption agency was established at the request of the EU, its independence is in question and it has not been given investigative powers to deal with high-level corruption, which remains unpunished. Without significant reforms, Georgia is expected to sink further into a kleptocratic style of government.

Kazakhstan (39) is making some progress in tackling corruption issues, including legal reforms and the recovery of stolen assets. However, these efforts are overshadowed by autocratic governance with a lack of transparency and judicial independence. This, together with the enduring influence of powerful political elites, allows corruption to flourish.

To make significant progress, Kazakhstan must make its anti-corruption initiatives comprehensive, transparent and free from political interference, while ensuring broader democratic reform.

Turkey’s (34) sharp drop of 8 points since 2015 is the result of too much executive dominance and few democratic controls. Inadequate anti-corruption laws, unwillingness to enforce laws and lack of judicial independence stand in the way of progress. The tragic consequences of the earthquake in February 2023 showed that the price of corruption is sometimes paid in human lives.

Serbia (36) is witnessing the decline of democracy, with the autocratic government using special laws to limit transparency in large-scale projects. A recent law exposed at least one billion euros of public funds, earmarked for Expo 2027, to the risk of overestimated contract amounts and poorly executed works.

The prosecution also did not respond to publicly presented evidence that election fraud benefited the ruling Serbian Progressive Party and its allies in December 2023. This political capture of judicial institutions fails to protect the public interest at a crucial time, reducing the country’s ability to fight corruption.

Montenegro (46) shows how prior capture of the state can leave lasting consequences on institutions. After three decades of one-party rule, ending in 2020, many were encouraged to report past corruption.

However, the slow progress in prosecuting these cases and the struggle to restore a functioning judiciary reveal how deeply entrapment by the former regime and organized crime has destroyed the justice system.

These weaknesses also demonstrate the government’s subsequent inability to implement decisive reforms. In order to be successful, the coalition government led by the political party Europe Now! must make the fight against corruption and organized crime a priority.

Country to observe: Kyrgyzstan

In just four years, Kyrgyzstan, 26, has transformed from a bastion of democracy with a vibrant civil society into a consolidated authoritarian regime that uses its judicial system to target critics.

This contributes to an increase in the level of corruption, which shows a five-point drop in the corruption perception index since 2020. The transition of President Sadyr Japarov to the presidential position further strengthened his control over the country.

His repressive and authoritarian way of governing deviates from legal procedures and constitutional norms, undermines civil liberties and enslaves democratic institutions. He has undermined the independence of the judiciary from national to local levels, including influencing key judicial appointments and the State Committee for National Security (GKNB), which has played a key role in cases of high-level corruption.

GKNB has become a completely closed instrument for stifling political opponents, independent media and critical voices. Inappropriate influence on the judiciary, together with the ineffective application of anti-corruption laws, undermines the rule of law and makes it difficult to effectively deal with corruption cases. This fosters a culture of impunity for abuses of power throughout the public sector.

Other authoritarian trends further undermine accountability. These include a significant decline in government transparency, preventing journalists and the public from uncovering irregularities and increasing the risk of corruption. Of particular concern are recent changes in public procurement laws that allow state and municipal enterprises to bypass tender procedures and retain information about their spending.

Kyrgyzstan’s leaders must urgently recommit themselves to democratic principles, ensure the independence of the judiciary and effectively enforce anti-corruption laws.

Early steps towards integrity

In the two years that followed the “Velvet Revolution” of 2018 , Armenia (47) experienced significant democratic and anti-corruption reforms. However, progress in the fight against corruption has stalled, mainly due to the limited implementation of new measures.

Despite facing challenges in terms of security – like many countries in the region – Armenia has the potential to deal with such difficulties and turn strong policies into better control of corruption.

Ukraine (36) advanced by three points this year on the Corruption Perceptions Index, continuing its eleven-year rise. This happened as Russia’s war against the country posed huge challenges to Ukraine’s governance and infrastructure, increasing the risk of corruption.

The focus on judicial system reforms, including the restructuring of self-regulatory bodies and increasing the independence of the judiciary, was crucial. Efforts to strengthen the capacity and independence of its anti-corruption agencies (NABU) and its anti-corruption enforcement body (SAPO) – together with the national anti-corruption strategy and its comprehensive enforcement program – have provided a solid foundation for sustained anti-corruption efforts.

Progress is further demonstrated through the strong involvement of civil society, such as re-emphasizing the requirement that public officials submit e-statements of their assets. Public procurement in Ukraine is characterized as competitive, which is positively recognized by the World Bank.

The government’s efforts, especially in the area of reconstruction, have been key to fostering accountability and control.

Despite these improvements, the existence of a significant number of cases of high corruption remains a major concern. The government’s efforts to deal with high-level corruption, including firings and criminal prosecutions, demonstrate its commitment to solving the problem. It also shows that existing systems work and are capable of detecting such cases.

However, further challenges and the need for permanent and comprehensive anti-corruption measures are highlighted in order for Ukraine to achieve full reform and European integration.

Uzbekistan stands out in the region with a significant improvement in the CPI score of 33 (+15 since 2014). Key steps include creating an anti-corruption agency, strengthening legislation and liberalizing the economy.

It is important to note that policies and procedures have been established to implement these laws, and criminal charges have been filed against numerous corrupt officials. The government has also introduced stronger internal control and audit tools in various ministries and local governments, such as the anti-bribery management system.

However, authoritarian governance hinders steps towards transparency and democracy by controlling legislative and public institutions and using the judicial system against critics.

This perpetuates corruption and underscores the need for comprehensive reform.

The democratic progress that Kosovo (41) has achieved, especially in terms of free elections and a peaceful transfer of power, still needs to be followed up with action against corruption. Despite ongoing efforts, key reforms for independence in the judicial system, such as the establishment of an evaluation procedure for judicial office holders and the adoption of a new law that could strengthen the integrity of the State Council of Prosecutors, are proceeding very slowly.

Moreover, the government’s constant interference in the work of the judiciary, which can be seen in the dismissal of the head of the police department for special investigations, along with the obstruction of the majority of parliamentarians in the investigation of an alleged major corruption case, suggests that the political will to relinquish control and strengthen independent oversight is still not present.

Albania (37) is improving its record with investigations and prosecutions of high corruption, but further progress depends on strengthening criminal legislation and ensuring effective oversight of the executive branch. The decision to establish a new ministry responsible for anti-corruption activities comes with the expectation of effective integrity mechanisms.

However, this cannot be achieved if the parliament does not have stronger autonomy, and civil society organizations and the media cannot perform their oversight role without interference from the authorities.

Get involved

Stay tuned

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive periodic notifications about our, announcements, calls and activities via email.

Don't miss it

If you want to receive our announcements immediately after the publication, leave your e-mail address in the field below.